Author: Mirela Dialeti

As screens accelerate our attention and algorithms dictate what we see, a quiet rebellion is unfolding in ink and paper. Independent artists and collectives across Europe and beyond are returning to handmade books and zines—not out of nostalgia, but as acts of resistance. For them, the printed page is not just an object but a living encounter: touch, time, and attention bound together in defiance of platforms and economies that compress art into content.

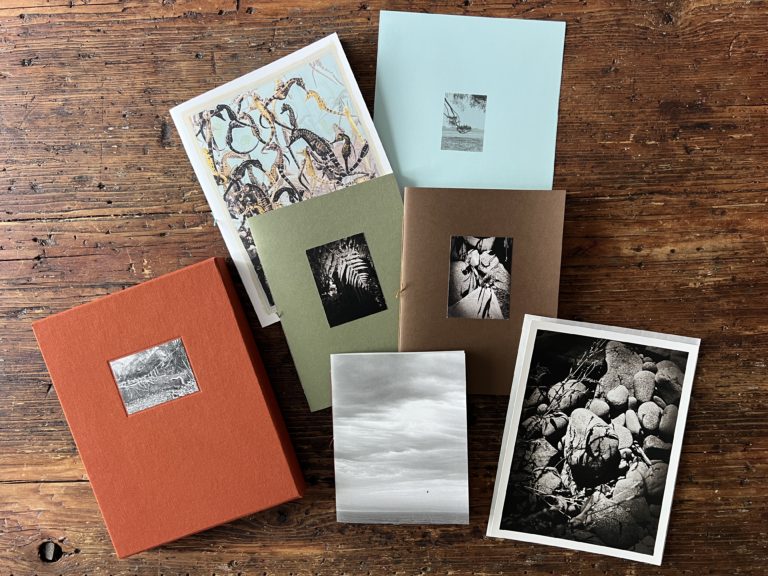

Zoopark Publishing Workshop Photobooks, Switzerland 2023

It starts, as so many obsessions do, with touch.

The first time I held a handmade zine, years ago, it didn’t feel like a product, but like meeting someone new. What was it that created this feeling, this sense that in my hands lay the possibility of a new friendship? “To see takes time, like to have a friend takes time,” Georgia O’Keeffe famously wrote about the art of seeing[1]. My friend’s paper was cheap and the binding imperfect, but taking the time to turn those pages, to pay attention to someone’s materialised thought, reshaped that moment of my life into a particular form of being.

Touch remains one of the most important ways we experience the world. From infancy, it is how we first communicate with our surroundings. Touch is also, more so undoubtedly today, a way to pay attention. Combine touch with time and you get the lived experience of a printed book, a universe contained between your palms.

That the promise of independent analog publishing today is not nostalgia or retro chic, but resistance, is something that does not really come to mind easily. Democratisation of content through digitalisation has brought unprecedented possibilities to artists—and yet— artistic freedom is more than ever under threat, not only from overt censorship but from economic structures that make creators dependent on platforms, patrons, or corporations with commercial or political agendas.

Across Europe and beyond, a loose constellation of artists is rediscovering the book and zine as living, free forms. Among them are Zoopark Collective, the duo Tatyana Palyga & Alexander Bondar, publishing together for more than a decade; Regina Maria Anzenberger, artist, curator, and founder/director of the Anzenberger Agency; and Tamsin Green, London-based artist and designer, founder of manual.editions, a non-profit dedicated to researching, designing, and making ecological photobooks.

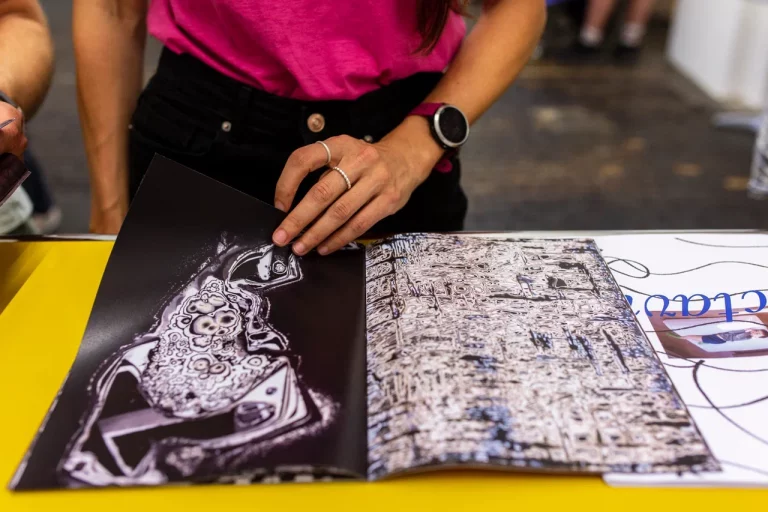

Regina Maria Anzenberger, Collector’s Edition box with four booklets and a print from The Australian Journey

It Starts with Touch

All three publishers I spoke with circle back, again and again, to the physicality of books. “The physical aspect plays an intrinsic role in a photobook or zine,” Tatiana Palyga from Zoopark Collective explains. “As an object you hold in your hands, it adds to the perception of the project inside. Every little detail says something about your work.”

Regina Maria Anzenberger from Anzenberger Agency also echoes that sense of necessity. After decades of painting, she turned to photography in 2011, and books followed naturally. “A book is perfect to tell a story,” she says. “And I think to understand a story it is better to have something physical in your hand and take the time to look carefully through it.”

She goes further: “I started to print on old printing machines again because of the smell of the colour on paper. You do not have it on modern UV printing machines.”

For Tamsin Green, the woman behind manual.editions, the embodied process of reading and handling the book is integral—it shapes the way connections are formed and understood. “The book medium provides a structure for examining and combining things together to create connections as part of an embodied experience of the world…Books by nature are linear, but visual books in particular provide the possibility for non-linear reading, people can dip into them, meander, or read backwards. Of course, these different readings are not limited to physicality, but are also situated within a worldview. I see great potential in visual books to challenge Western linear narratives and histories, to unpick them and to imagine otherwise”.

Zoopark: When Photobooks Travel

For Zoopark Collective, self-publishing was less about a manifesto at first and more about curiosity. “We are both photographers and self-publishing when we started was an opportunity to see our photography in a different way, to show it in a form of an object that can travel, can be handed from one person to another, can be seen multiple times and be an affordable art piece,” Tatiana recalls.

Founded in 2016 by Tatyana and Alexander, Zoopark Collective travels Europe to give workshops to photographers and artists who want to publish independently.

In their telling, there was little faith in the mainstream. “In parallel to self-publishing we tried to reach some publishers, participated in some portfolio reviews, but that gave no results. Some publishers required us to bring our own funding to cover the printing cost which made publishing projects very costly and unaffordable,” Tatiana says.

Zoopark’s workshops across Europe and beyond underscore these dynamics of artistic dependence. European participants often come with prior knowledge, access to funding, and the choice to self-publish or work with publishers. In Morocco, where they held one of their last workshops in February 2025, the process was entirely new: making a book is challenging, resource-limited, and intuitive. Alexander reflects that creative freedom exists everywhere, but what one can do with it depends heavily on the ability to achieve economic independence—grants, printing costs, travel, and visas all shape what a person can bring to completion. “Freedom is freedom,” he says, “but then comes the next step: what you do with it—and that’s heavily influenced by your financial independence.”

Zoopark Publishing Workshop Photobooks, Switzerland 2023

Against the Feed

The digital space, meanwhile, is both a tool and trap. For some, it remains useful. Regina insists she sees “more new possibilities than limitations” in online spaces, noting that social media has allowed more artists to self-publish and market books independently.

But Zoopark is more cautious. “In independent or self-publishing, it’s the artist who creates the rules,” Tatiana says. Bigger publishers, she notes, chase what sells.

Just as the economic retreat of journalism hollowed out once powerful media institutions and created fertile ground for disinformation, the retreat of cultural funding and independent publishing has left artists vulnerable to capture. When independent galleries, presses, and cultural institutions weaken, vanish, or are starved of resources, their absence creates a vacuum that digital platforms rush to occupy—platforms where creators turn in search of artistic freedom and independence, but often find themselves bound instead by new forms of dependency. These platforms claim neutrality but wield tremendous power, their priority not being cultural plurality but profit and influence. They own the data, control audiences, and thus become gatekeepers over what gets seen—or what is silenced.

The conditions that allow disinformation to flourish—weakened independent organisations and monopolised digital spaces—are the same conditions that erode artistic freedom. Gatekeeping and content moderation on social media may seem necessary, but a lot of times they are flawed; the label “harmful” often applied to precisely the work that challenges power or provokes reflection. The result is a cultural ecosystem where the work most needed to provoke reflection or resistance is pushed to the margins.

Hand, Heart, and the Planet

If Zoopark embodies the rebellious DIY spirit, Tamsin Green insists that rebellion also carries responsibility—to the environment, to the materials themselves.

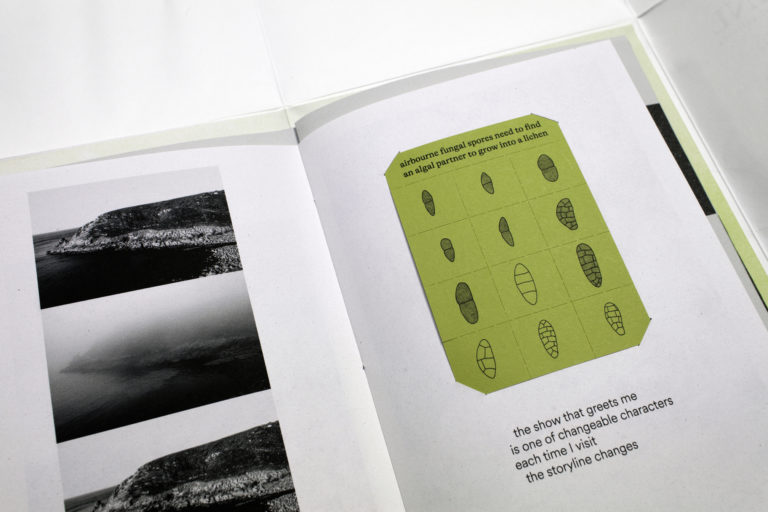

“I have always been fascinated by printed matter,” she says, recalling time in Tokyo bookshops studying bindings and paper, which deepened her practice. “Publishing a book mobilises many processes that connect to both local and global ecologies through materials, money, labour, and transportation. The choice to work with digital or physical media, or a combination of the two, is one that needs to be considered holistically, both have their impacts. So, if we are going to make books, how can we develop creative practices that consider ecological sustainability at each step of the process?”

Her own answer was to found manual.editions in 2021, as a platform for publishing, lending, and convening the Sustainable Photobook Publishing network.

This embodied approach extends, as we saw already, to her craft: “I assemble and bind all of the books by hand. This process makes me very aware of the nature of the materials I am working with and the waste produced through the making process. Each project often tackles issues that arose in the last, and so in this way they are constantly evolving.”

For her, to make a book is not just to tell a story but to participate in an ecosystem.

walking out of sleep, encounters with lichen territory by Tamsin Green, published by manual.editions, 2023

A Way to Reimagine

So where does all this leave us? For some, like Regina, the future looks more open than closed. “Self-publishing is a great option,” she says simply. “It gives you more control, and in the end, you can even earn money instead of just spending it.”

And for Zoopark, the future remains in experimentation, play, and the stubborn act of making.

“Ethics is about paying attention,” says Tamsin, “asking questions, feeling your way through gaps in your own knowledge, and being open to unlearning. It requires humility, listening, and embracing the different paths that may be presented through these different ways of working”.

In a world where digital feeds filter our every glance, the book is more than a format. Weight in the hand, time on the page, a surface that resists the swipe, a way of really paying attention, to unlearn, and to defy the curated visions sold by those who grow wealthy by narrowing our imagination.

A way to imagine, again, the possible.

[1] Elizabeth Hutton Turner & Marjorie P. Balge-Crozier, Georgia O’Keeffe: The Poetry of Things, Yale University Press in association with the Dallas Museum of Art, 1999

Published on October 6th, 2025

About the author:

Mirela Dialeti is a Brussels-based journalist and communications professional from Greece with a background in law and investigative reporting. She focuses on digital rights, feminist policy, AI ethics, and cultural narratives. Her work includes reporting on violence against women, data privacy, arts and culture, and EU politics. She also conducts interviews with artists worldwide and covers cultural events across Europe.