A Roundtable

Author: Zain Salam Assaad

In the face of mounting political pressures and funding cuts, independent cultural initiatives led by BIPoC and migrant communities in Germany—especially in the East—are confronting new and intensified challenges. As right-wing movements gain traction, projects like Leipzig’s Narratif Magazine, JUGENDSTIL*, and artist-led collectives are finding ways to sustain their work, navigating a volatile landscape with resilience and creativity. This roundtable discussion brings together key voices from Saxony’s grassroots cultural scene to explore how they adapt, resist, and continue to carve out spaces for artistic and political expression despite obstacles.

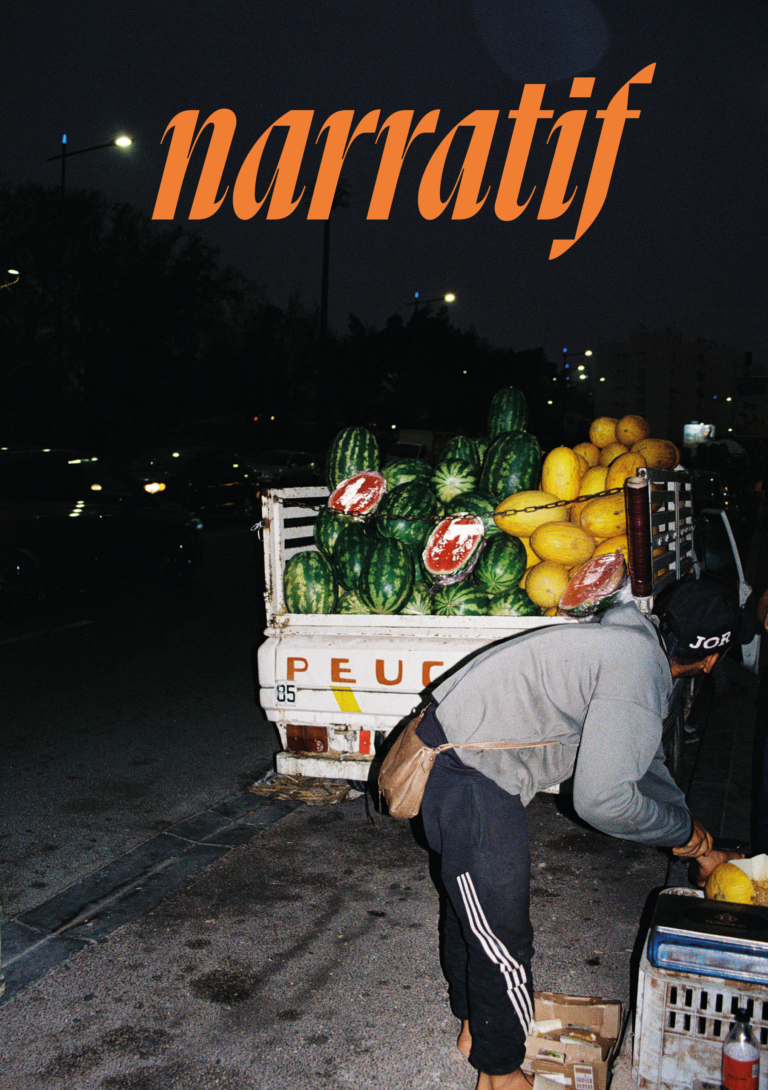

Narratif Cover NM Paradies Aussen

As right-wing mobilisation and funding cuts reshape Germany's cultural landscape, independent initiatives led by BIPoC and migrant communities face mounting challenges—particularly in Eastern Germany, where these struggles take on heightened significance. How do these efforts navigate an increasingly volatile climate? What drives their resilience, sustains their impact, and connects the threads of grassroots networks across the region?

This roundtable brings together three influential voices from Leipzig and Saxony’s independent cultural scene: Yasemin Said, editor at Narratif Magazine, a free arts and literature publication born out of PERSPECTIVES, a Leipzig Grünau neighborhood project. Narratif amplifies creative work rooted in migrant and local experiences, with its second issue released in December 2024. Walter Grunt from JUGENDSTIL*, a project by Stiftung Bürger für Bürger, creating funding pathways for migrant and BIPoC youth in East Germany. al-Kalamah Hammam Alawam, an artist and researcher whose work bridges performance and curation. Together, they navigate the realities of cultural work in East Germany, uncovering shared struggles, creative strategies, and necessary visions for reimagining independent cultural spaces amidst adversity.

Zain Salam Assaad: East Germany’s turbulent political legacy is back in the spotlight—with right-wing radicalisation and election results stirring up debate. You work in political hotspots like Saxony and Thuringia. How does this climate shape your day-to-day projects, and what challenges—or maybe even opportunities—are you facing in your work?

Yasemin Said (Narratif Magazine): The political environment has a very real impact on our work. Narratif is part of PERSPECTIVES that is entirely funded by the state of Saxony through the Saxon Development Bank. When the AfD initiated an investigative committee to review how funds are allocated, they gained access to personal data about our staff and volunteers. That was a wake-up call. It put us under a microscope, forcing us to think carefully about things as basic as whether certain magazine submissions could jeopardise our funding. You can see the fallout in other groups, like the Saxon Refugee Council, which lost its support without a clear replacement.

Walter Grunt (JUGENDSTIL*): When I think about recent setbacks, the questionable dissolution of the DSM (Association of Saxon Migrant Organisations) immediately comes to mind. Overnight, this move erased a vital support system for at least 66 migrant initiatives. Our own research at JUGENDSTIL* highlights the gravity of the situation: around a quarter of the organisations we work with have faced physical attacks simply for standing up for their communities.

al-Kalamah Hammam Alawam (Artist and researcher): From a funding perspective, as an independent group of artists, we initially had limited experience with external grants and handled almost everything on our own. We mostly collaborated with institutions like the Grassi Museum and are now preparing for a project in Chemnitz as part of its 2025 European Capital of Culture programme. But lately, we’ve started applying for grants, which is quite different from working directly with institutions—especially amid shifting political climates. Honestly, tackling sensitive topics in this context isn’t always easy.

Yasemin Said: I’m not a huge fan of the term ‘rightward shift,’ especially if you’ve grown up in Saxony—these attitudes have always been around. But now they’re on full display, and that’s changed how we operate and plan the magazine’s future.

Walter Grunt: On a more personal note, in my one-on-one advisory sessions, I’ve heard multiple stories of people being harassed or even assaulted, for example on trains—a worrying development that seems to have intensified over the last few months. Given the current climate, these challenges are only growing—which is exactly why we must speak out and act now.

al-Kalamah Hammam Alawam: We experience these tensions on multiple levels, given that our work often tackles themes like ethnographic representation and other politically charged topics such as social and political issues around the Middle East, or identity politics in Germany. We knew from the outset that this could be problematic, but we forged ahead anyway, ready to adapt if things got difficult. We’ve learned to stay strategic: if one route closes off, we’ve always got a backup plan ready to go.

Yasemin Said – © Tansu Kayaalp

I sense a growing sense of risk in your experiences right now, not just in creating your own workspaces, but in finding places that fully embrace who you are and what you do. Given these challenges, how do you find and maintain spaces for your work?

al-Kalamah Hammam Alawam: Absolutely, it is tough out there. We have built strong connections, such as with Grassi Museum and we recently curated a show at the HGB Gallery. However, some opportunities simply disappeared without warning, which shows how precarious this field can be. That risk has always been there, and it feels even greater now. Despite these setbacks, we focus on creating new avenues and partnerships.

Yasemin Said: We’ve always prioritised spaces where we have personal connections. For example, our release event for the new Narratif Magazine edition will take place at a bar run by friends. It’s a choice that allows us to work without the stress of external pressures. Honestly, this approach hasn’t changed much over the years. From the beginning, we’ve been selective about venues, avoiding places that didn’t feel right. When we collaborated with a major museum in Leipzig, it was a complete flop, though not entirely surprising. We gave it a try, but as a smaller project, large-scale partnerships have never been our focus. For us, it’s all about trusted, familiar spaces where we can stay true to our way of working.

Walter Grunt: Here, I find it important to highlight that while monitoring the actions of extremists and the AfD is important, the conversation has broadened in a troubling way. We're frequently asked how young migrants in East Germany can counter the AfD, which narrows our mission. This focus means that artists who want to explore other themes often struggle for funding, attention, and exhibition spaces because the spotlight is so heavily weighted towards anti-AfD efforts. It’s not just a fringe issue; this shift is redefining the entire scope of action for migrants in East Germany. This extremist agenda is taking control of the narratives of diverse cultural voices, and it’s a trend that’s both frustrating and hard to encapsulate in a single word.

How does the political pressure at the moment translate into your work? Have you ever felt compelled to self-censor to avoid repercussions?

Yasemin Said: Unfortunately, yes. I’d say that when we were working on the introduction for our newest issue and with some of the submissions we received, we had to seriously ask ourselves if publishing them was even realistic. We worried about losing our funding, so we played it safe, which is basically a form of self-censorship. We tried not to blow it out of proportion because we know we have an amazing opportunity with this magazine. Maybe we were just telling ourselves it was still worth it. But let’s be real: it’s weird when you hold back because you know it could cause trouble. I mentioned the investigative committee before, and we’ve all become a lot more cautious since then. But honestly, I’m not sure if we’re really any more cautious than before. From the start, it was obvious we’re funded by the Free State of Saxony, so we’ve always had to watch what we say.

Walter Grunt: We help initiatives present their ideas in ways that resonate with funders. It’s not exactly censorship; it’s more about hitting the right notes using certain keywords like “diversity” to secure support. That’s a separate conversation from actual self-censorship. Internally, tailoring our approach to specifically reach our target audience wasn’t a problem. A key factor was that our project team doesn’t handle funding decisions. Instead, we’ve elected a youth jury composed of young migrants living in East Germany who make all funding decisions independently. This ensures our funding process is authentic and detached from funders’ expectations.

Yasemin Said: For me, the question of funding is closely tied to taking on responsibility. With our project, we quickly prioritised our specific audience and their future development over broader goals like democracy promotion. In light of current cuts and pressures, I often think of Berlin’s Spore Initiative, which is funded entirely by private donations. While I believe funding should primarily be a state responsibility, relying on government funds can lead to self-censorship and unstable support. In Germany, there’s a common assumption that state funds are neutral compared to private ones, but that’s not always the case. Looking ahead, while our funding from Narratif is secure for another year, we may soon need to turn to private donors to safeguard our editorial independence.

Self-portrait – © al-Kalamah Hammam Alawam

How vital are community networks and support systems, particularly among migrant communities, to your work, and how do you see your reliance on them evolving in the future?

al-Kalamah Hammam Alawam: There’s definitely a dynamic migrant cultural scene spanning all kinds of fields. Our team alone includes people from places like Syria and the U.S., and we collaborate closely with local communities. We work with people from migrant or post-migrant backgrounds—or really anyone who’s come from abroad. There is support out there, but it’s not super organised, so it can be tough to find the right info or resources. Still, there is a real willingness to connect in a loose, community-driven way. You’ll see different groups and individuals helping each other out in various channels across the cultural scene. A lot of unpaid labour involved!

Yasemin Said: For us, this network is intrinsic to our work. Our magazine is very much a peer-to-peer project—our target audience is essentially us, so it’s a shared experience. However, funding constraints and reliance on unpaid work highlight the limits of such networks. On the one hand, it’s inspiring to see people so committed and willing to contribute with their time and energy. On the other hand, it’s hard to ignore that this often borders on self-exploitation, which deserves criticism. Financially, we simply don’t have the resources to structure it differently, and the team was largely okay with this from the start, knowing the risks of running out of funding entirely. Despite this, I think the magazine has opened doors for some of us—whether it’s being able to say, 'Hey, I worked on this,' or having a platform to showcase writing that others can recognise and value. In certain creative and cultural scenes in Germany, that kind of visibility matters. So, while the workload can sometimes feel overwhelming and unpaid, it’s also been rewarding to see the opportunities it creates.

Walter Grunt: Our study on post-migratory engagement in East Germany shows that most people volunteer out of passion or necessity, creating their own safe spaces and platforms—not just for career advancement, but very much for survival.

al-Kalamah Hammam Alawam: The tough part is, in art school, nobody teaches you any of this. No one shows you how to write a grant application or even where to send it, especially if you’re from a migrant or international background. A lot of folks don’t know how to tap into those smaller grants. It’s definitely something you have to pick up along the way. I’d never really dealt with organising events, performances, or curating programmes before. I just didn’t know how. And if you don’t even realise it’s an option (or how complicated it might be), you never try, right? Before, I’d collaborate with art associations or clubs, and they’d fund my work directly. But at some point, I thought, “We want to do this on our own,” so I had to learn the ropes. Now I feel like we’ve got it down. We know how to write proposals, and we’re even thinking about starting our own art organisation.

Walter Grunt: JUGENDSTIL* has been around for nearly five years, and I think we’ve really filled a gap. We created a straightforward, low-barrier way to fund small groups, even those without official non-profit status, and made a point of reaching out directly to young people with migrant backgrounds and BiPoCs. We show them it’s worth applying, and we bring them together to share their ideas. It’s had a big impact: we’re seeing more projects led by people who might never have gotten funding otherwise. Now, plenty of newer organisations are picking up pieces of our model or consult with us before they start handing out grants. Making sure migrant communities are front and centre has become less of an afterthought, and I’d say that’s been JUGENDSTIL*’s biggest success.

Walter Grunt – © JUGENDSTIL*

What changes or support do you think are necessary to improve the situation for your work and others like you?

Yasemin Said: Lately, I’ve been wondering why more people aren't stepping up to address the serious challenges we face. I believe that organising into groups and getting politically active can provide much-needed solidarity. It’s not just about explaining our work to others but reminding ourselves that we’re not alone in our struggle. We need communities with shared goals.

al-Kalamah Hammam Alawam: Understanding underlying structures is crucial, especially for marginalised and migrant artists. We need effective strategies to navigate today’s challenging political landscape and keep moving forward without getting stuck in endless debates. I believe in the power of collective effort. Collaboration leads to unexpected and valuable outcomes that aren’t possible alone. Building connections with others working on these issues is impactful. It helps us manage time and energy efficiently to prevent the state of constant burnout.

Walter Grunt: The first word that comes to mind is courage. I hope migrant communities find the courage to bring their ideas to life, build their own structures, and think creatively about how to sustain them. For those in power, I wish for the willingness to step back, share knowledge, and break down hierarchies. After all, hierarchies thrive on exclusive knowledge, and dismantling them requires collective action, not just from migrant communities but from everyone.

JUGENDSTIL* event – © Cristobal Z Arellano

Behind the Words

Yasemin Said (she/-), born in 1993, is a freelance journalist, director, and documentary filmmaker. Her work critically explores the power dynamics between filmmakers and their subjects, striving for innovative narrative forms. Beyond her journalistic endeavours, Yasemin is committed to political education and community initiatives, having founded the PERSPECTIVES project in Leipzig. She is also part of the editorial team at Narratif Magazine.

Al-Kalamah Hammam Alawam (he/him) is a Syrian artist from Swaida, currently based in Leipzig. As a transdisciplinary artist and curatorial researcher, Alawam holds a diploma in Performance Art and Photography from the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst Leipzig.

Walter Grunt (they/he) works at JUGENDSTIL*, where he co-developed funding programmes that have supported over 100 young migrant initiatives in East Germany. Additionally, Walter actively participates in the Asia-German community, notably by running a film club.

Published on February 11th, 2025

About the author:

Zain Salam Assaad (no pronouns) is pursuing a Master’s in Global Studies, studying in both Berlin and Buenos Aires. As a freelance journalist and translator, Assaad specialises in LGBTQ+ rights, migration, and digital trends. For Missy Magazine, Assaad authored the monthly column "Hypertext," delving into pop culture and socio-political developments. Currently, Assaad is a fellow with the Friedrich Ebert Foundation and a Democracy Fellow within Humanity in Action’s transatlantic network, where their research focuses on memory politics in the context of Syria.