Author: Željko Maksimović

On November 1st, 2024, a tragedy shook Serbia when the newly renovated roof of the Novi Sad railway station collapsed, killing 15 people instantly and injuring several others—one of whom later became the 16th victim. What began as what could seem like an accident quickly ignited a wave of outrage that turned into the largest protest movement in the country's history, driven by students demanding justice, accountability, and an end to corruption. Their fight, echoing far beyond the crumbled concrete, has since evolved into a nationwide reckoning with political power and media silence in Serbia, and Europe.

Protest in Belgrade – © Ivana Todorovski

On November 1st, 2024, the concrete roof over the entrance to the railway station in Novi Sad—Serbia’s second-largest city—collapsed, initially killing 15 people and severely injuring 2 (one of whom, an 18-year-old boy, died on March 21st, making him the 16th victim). The station had previously been renovated as one of the many controversial and overpriced construction projects promoted by the government (the price was raised from 3 to 16 million euros) and pompously opened by the president and other high officials (ironically, under the same roof). The people of Novi Sad took to the streets to demand accountability—unknowingly starting the largest protests in the history of Serbia.

The Student Beginnings

The president and the minister of Construction stated the roof hadn’t been rebuilt. University students and citizens in the three largest cities (Belgrade, Novi Sad, Niš) blocked major road intersections, held silent vigils for the victims, and spread their outrage on social media with hashtags such as #JusticeForTheFifteen and #StopCorruption.

On November 22nd, students and professors from the Faculty of Dramatic Arts blocked the road in front of their school but were attacked by angry passers-by who turned out to be local officials from the ruling party. As a result, the students blocked the school and refused to leave until the perpetrators of the attack were brought to justice. Officials dismissed the protests as political, while national broadcasters largely ignored the situation. The university students’ blockade quickly spread to all state schools, including primary and secondary schools. The silent vigils were and still are held every day at 11:52am, now lasting 16 minutes in honour of the 16 victims. Angry passers-by began verbally and physically attacking the participants, and angry drivers ploughed their cars into the crowds, injuring several (mostly female) students. Around 20 attacks were recorded[1], with most of the perpetrators (again) connected to the ruling party. These incidents brought even more people onto the streets across the country. Student actions now include hours-long blockades of major roads, exhausting marches across the country (some around 200km long), and massive protests in different cities (gathering hundreds of thousands of people). Locals are welcoming the students as liberators, organising places to sleep, and preparing impressive amounts of food.

Protest in Belgrade. On the signs: bottom left hand corner Devojčice na ulice. Blokade do pravde (Girls on the streets. Blockades for justice) / Top right hand corner Руже су црвене, љубичице плаве, јавне нам зграде падају на гдаве (Roses are red, violets are blue, our public buildings are falling down) – © Ivana Ivković

The EU Gap and General Silence

Months into the protests, there is still no end in sight. The opposition has blocked local parliaments in several cities, however the core of the movement, the students, continue to distance themselves from all political parties. This resentment of political actors has been a defining feature of the ruling Progressive Party's (SNS) influence on the political atmosphere in the country—its decades-long propaganda against the opposition, although many of its high officials are former democrats, and the machinations it employs in every election (e.g. fake opposition joining the ruling coalition immediately after the elections) make it essential for any protest to be dissociated from all parties. I will not go into the origin story of SNS, the former radicals (nationalists), but I will say that its beginnings resemble the rise of any populist option (Trump, Le Pen, AFD, etc.) that gains momentum after a democratic government has failed its citizens. With Serbia classified as partly free in the latest Freedom House report, we have to ask the million-dollar question: why is the EU silent? Why does its Commission’s president rush to support the Georgian uprising but completely ignore Serbian students? If Madonna (yes, the pop star) found the protests relevant enough to share on her Instagram (along with other celebrities), why didn’t von der Leyen? Maybe she’s got bigger wolves to fight?[2]

One possible answer could be found in Angela Merkel’s farewell tour during her visit to Belgrade. At a joint press conference with the Serbian president, to which independent media were denied access, Merkel announced Germany’s intention to explore for lithium in Serbia[3]. Lithium exploration has caused massive protests in the past because, according to numerous expert reports, it could lead to an environmental disaster in the region. Another answer may lie in the authenticity of the student revolt, meaning that it seems as a grassroot uprising, not as an engineered event (while the October 5th, 2000 revolution that brought down Milošević is often seen as foreign-sponsored). Despite the efforts of the ruling coalition to portray it as “a colour revolution”, there is a sense that genuine disillusionment with a corrupt system has erupted and infected not just the students, but other social groups. “We are all under one roof,” said a protester, perfectly summarising the living conditions not only of Serbian citizens, but of anyone living in post-industrial capitalism. Is this universal sentiment powerful enough to spill over into other societies, as it did in 1968? Could this be the reason why the mighty have fallen silent?

I can understand that, from an editorial point of view, Serbia is too small for the international media to make headlines, but why did it take the illegal use of an alleged sonic weapon against peaceful demonstrators and a camp of fake students surrounding the presidency building for them to take notice? Seeing how the traditional media simply repeated the officials’ positions and manipulated the facts when reporting on the genocide in Gaza carried out by a Western ally, I can only assume that they are following the EU leaders’ silence in the case of Serbia as well. This can also answer a question often asked by the citizens of the European Union—why are there no EU flags at the Serbian protests? The ruling coalition’s total disregard for the rule of law, control of the media, promotion of pro-Russian sentiments and Chinese investments, combined with the European People’s Party group’s protection of its Serbian partner—the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS)—from any harsh criticism, led to the historically lowest support for EU integration in the country.

We had the largest protest in the history of the country on March 15th in Belgrade, called 15th for the 15 (the 16th victim came about a week later), where the most conservative estimates say that over 300,000 people took to the streets, while some put the figure as high as 800,000, and this is the first time in 4 months that we see coverage in numerous languages. So it took 5% to 13% of the total population to get the attention of the news agencies. This shows how traditional media can influence our reality and silence our voices. But the students are finding ways to make their voices heard—some have cycled from Novi Sad to Strasbourg to speak to EU representatives, and have announced plans to march on Brussels.

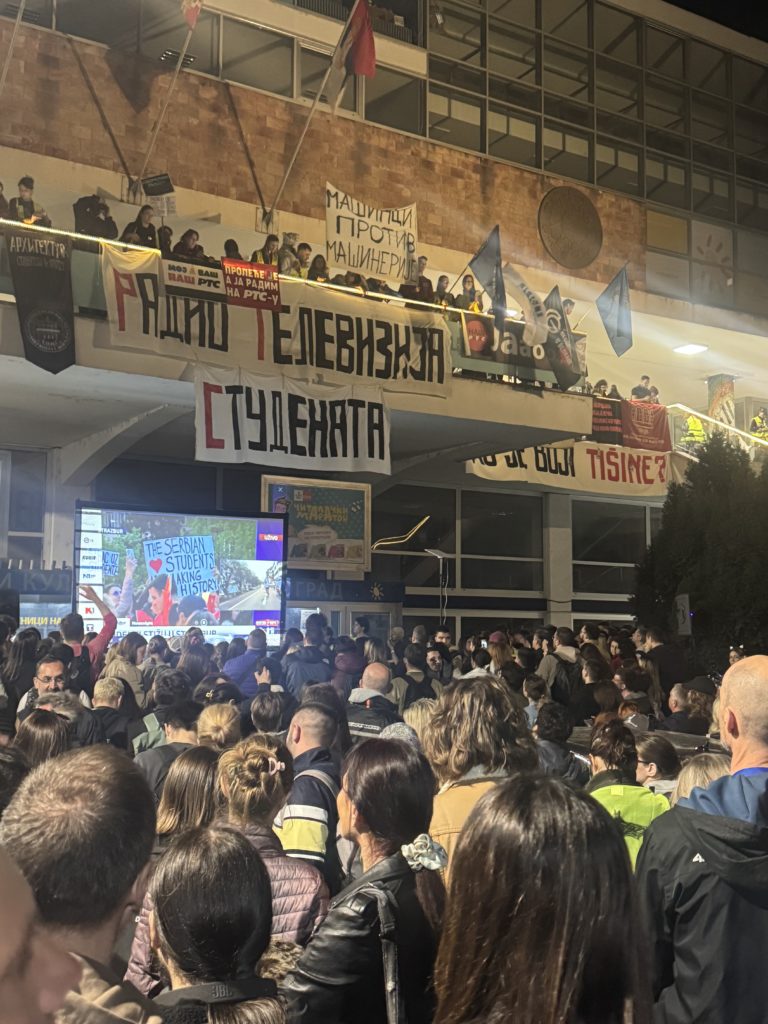

Blockade in front of the Radio Television of Serbia in Belgrade, state-owned public radio and television broadcaster. On the main sign: радио телевизија стчдената (Radio and Television of the Students) – © Ivana Ivković

The More, The Better

But what the students have taught us is very important—numbers protect us, empathy and solidarity are essential, and unity is stronger than oppression. This unity that their actions have managed to create in the Serbian society has had tangible effects. For instance, uniting people to bring down the 2.5 million follower Instagram account of a famous former critic-turned-main-propagandist, a singer who began praising the president after her latest album was allegedly heavily funded by the National Telecommunications Agency[4].

The movement also brought the IT sector—one of the country’s more financially stable professions—to raise huge sums of money to support striking teachers whose salaries have been illegally cut by the Ministry of Education for supporting the student movement. Most importantly, it continues to free people from fear, because if you are arrested, lawyers offer free legal assistance; if you don’t have a place to sleep in a city where a big protest is being organised, people offer their homes; if you get a flat tyre on the way to a protest, a mechanic will bring you a new one and fit it for free (this happened to a friend of mine); if you organise a big gathering in a public space, you can easily clean the space if everyone helps, and this is exactly what students do after every protest.

They have shown us that this form of organisation, where people share their resources and where every voice counts—which they do through plenary sessions or plenums in their schools, but they have also proposed citizens’ assemblies, a legal form of public expression where citizens can discuss and decide on matters of concern to them, could be an alternative to the post-industrial capitalism as manifested in the neo-colonial appropriation of land and resources through deals between corporations and political elites. Their efforts have made us question whether representative democracy is democratic at all. Whether any human being can be trusted to serve the interests of a group of people without falling into the trap of corruption.

On the other hand, the fetishisation of plenums has also shown its downsides, and this refers to the cultural sector’s response to the students’ calls for support. There have been efforts within the sector to unite and act as a single group, but they have failed. I was part of an initiative, but I felt that the intentions of some members were not clear, the actions they took (the occupation of a cultural centre which, by the way, supported the students) were not well thought out and, most importantly, the plenums they organised were not democratic, i.e. not plenums at all. I felt deeply disappointed that the goal of overthrowing an autocratic regime (even the Guardian finally called the president autocratic in its recent coverage[5]) was sidelined for the sake of individual ambitions or egos, and that the historic opportunity to unite the heterogeneous and chaotic cultural sector was, if not killed, then dramatically postponed.

I have decided to end this reflection not on a high note, but with a caution—if anyone thinks that any people deserve what we have got with this regime (you voted for them, you’re not smart enough, you’re not part of the civilised world or— as the late American Secretary of State Madeleine Albright once called us—disgusting Serbs, etc.), think again and see what powers are rising worldwide. And remember, every voice counts, so unite to fight injustice. And pumpaj![6]

References

[1] "Armed thugs assault students in Novi Sad", N1, January 28th, 2025 ; "Dacic: It is an absolute lie that the students in Novi Sad were beaten by SNS thugs", Vreme, March 29th, 2025 ; Videos of attacks can be found here, or here

[2] Vučić comes from the name Vuk = eng. wolf, and can be translated as little wolf ; Louise Guillot, "Von der Leyen is campaigning hard — against the wolf", Politico, June 6th, 2024

[3] Michael Roick & Thomas Roser, "Deep gratitude and bitter disappointment", Friedrich Naumann Foundation, September 21st, 2021 ; "Merkel: Go further in legal reforms, pluralism; Vucic: Thank you for everything", N1, September 13th, 2021

[4] "‘Veliki bot’: Karleuša od Telekoma Srbija za novi album dobila milion i po eura?" ('Big bot': Karleuša received a million and a half euros from Telekom Srbija for her new album?), N1, August 16th, 2023 ; "Serbian folk singer Jelena Karleusa is suing N1", N1, August 20th, 2023

[5] Jennifer Rankin, "Protesters march in Belgrade at huge rally against Serbian president", The Guardian, March 15th, 2025

[6] Pumpaj (pump it) has become the leitmotiv of the protest, used to inspire everyone to keep their spirits up, and keep going.

Published on April 25th, 2025

About the author:

Željko Maksimović (1985) is an actor from Belgrade, Serbia. He appeared in several TV shows and short movies and is currently developing an experimental film with director Tamara Drakulić. He is currently performing in an award-winning performance The Regime of Love, written by Tanja Šljivar and directed by Bojan Đorđev in Belgrade’s Atelje 212 theater. Besides performing in numerous institutional theatres, he has also worked independently. Along with his friend and collaborator, theater director Ana Konstantinović, he leads eho animato art collective, creating works of experimental, multimedia, and digital theater, frequently collaborating with New York’s La MaMa theater. Since 2014, he has worked in Prague, Czech Republic, with the award-winning directorial duo SKUTR. Since 2019, he has been working with artist Ivana Ivković, participating in numerous of her delegated performances, both in Serbia and abroad. His other notable collaborators include renowned artists Selma Selman, Dušica Dražić and Doplgenger duo. He is also a translator, and his published works include essays on theatre theory and plays by Filip Grujić, Dino Pešut, and Tanja Šljivar, the latter in collaboration with a Berlin-based American artist Cory Tamler, published in the US by Asymptote Journal, The Mercurian and The Offing.