Author: Benjamin Sabbah

In a society defined by the relentless flow of information and the pervasive influence of mass media, the concept of a media ecosystem and the imperative of maintaining a plurality of independence have never been more crucial. The intricate web of news organizations, social platforms, and content creators that make up this ecosystem is a dynamic force shaping public perception, policy decisions, and even societal values. Yet, this intricate web is not without its challenges. Ensuring a diverse and truly independent media landscape has become a paramount concern, as concentration of media ownership and the proliferation of misinformation threaten the very foundations of a well-informed and participatory society.

While the massification of fake news has already revealed their ability to destabilise democracies, the concept of alternative fact has finished blurring the rules of the game between citizens, the media, and multiple sources of information–in the broadest sense–that have emerged on the web and social networks.

The level of trust that French people have in the media is deteriorating every year, so that today 54% of French people (according to the Kantar - La Croix barometer) believe that “we must be wary of the way in which the major issues of the media are treated.” This figure, which indicates that more than half of our fellow citizens doubt the organisations and people supposed to bring them elements to know what is happening in the world, understand, make decisions, is a disaster for our profession and a major problem for democracy. It is also a disappointment for all those who do this job with passion and whose independence is however put in doubt without evidence or discernment. Information is at the heart of what makes our society. This decline in confidence in journalists cannot be analysed outside of a general context of political and social tensions around the world. Relations with the media go wrong when relations with democracy go wrong.

In this particularly dense, fragile and anxious context, how can we try to rebuild trust between the media and citizens? Programmes, content, and technologies to combat fake news are multiplying and that’s good. However, the return on these colossal investments (given the often-delicate financial health of the media) is marginal compared to the size of the phenomenon. In designing and disseminating these initiatives, they will tend to reach people less likely to be exposed to fake news. Worse, for some people, the fact that it is denied by the media reinforces the credibility of fake news.

It is not only by doing what they know how to do–information, including investigation, reporting or the fight against fake news–that the media will regain the trust of citizens. It is also by explaining better who they are and how they work. The media is most often discredited by suspecting their independence. The same survey indicates that “59% of French people consider that journalists are not independent of political pressure and power.” That is why it is necessary to explain how an editorial board organises its independence.

Media and information: independence is one of the first criteria for reliability

Let us quickly note that no other form of business is expected to be independent. A company depends on its suppliers to provide it with what is needed to manufacture a product or service that it markets to its customers, sometimes through distributors, of which it depends just as much. It is generally among the regulated professions, in the non-market sector and in the political field that one is interested in the independence of associations, non-governmental organisations as well as the agencies and administrations of the State. We rightly believe that the mission of these families of organisations, which often aim to deliver a public good or provide a public service, must not be distorted or directed by investors with other interests.

To be interested in the independence of the media is therefore to recognise that the media are not economic actors like the others, that what they produce–information–has a public good value and a social value since information is the heart and soul of our discussions, that it is the basis of many of our decisions in the personal and professional aspects of our lives. To be interested in the independence of the media is also certainly to be vigilant and demanding in terms of the quality and impartiality of the information broadcast there.

With the term “the media”, we often include all media (television, radio, newspapers and magazines, the web), hundreds of businesses of a very different nature, object and size, and at least 35,000 journalists. The job of a newscaster and a video game journalist has little to do with each other, and yet both can be pressured about the treatment of the information they broadcast. Whether you are a citizen or a consumer, it is obviously legitimate to wonder whether what you are looking at or reading is true. Whether you can trust a face or a signature and the brand of the media that is affixed somewhere on the screen or paper.

In reality, there are many opportunities for a third party to influence editorial staff. We cannot say that all the media are independent in France today. In fact, some media no longer have a newsroom, or almost. Yet, the vast majority of the media have put in place rules that guarantee and require journalists to do their work with ethics. And the overwhelming majority of them do, no doubt.

Media and editorial independence: clarifying the term to complicate the debate

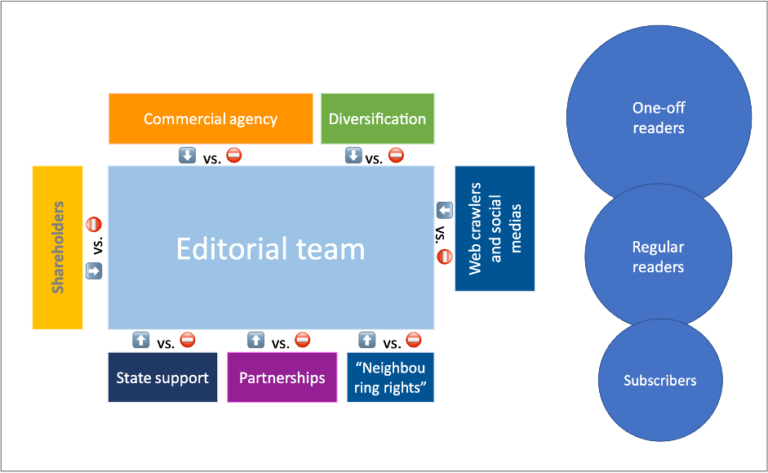

Given the diversity of models, each case deserves a little attention. In order to try to examine what independence a media must establish in order to protect the quality of its information, it is necessary to ask successively some questions about their legal form, their shareholding structure, their types of financing but also their distribution.

Diagram of the potential organisations of media © Benjamin Sabbah

Who owns the media? What is the link between the shareholder and the editorial staff?

Does the media examined belong to the State, a group of media, an industrial group, its founders–journalists or not–its readers, a fund, an association? Spontaneously, we can say that some form is more protective of the independence of an editorial board, such as membership of an association, a fund or its readers, than another that would be more harmful.

In some cases, the shareholder has a direct influence on the media’s editorial policy. When the media is run by its founders, themselves journalists, it seems quite logical. When the media belongs to a group or a State, the independence of editorial staff can a priori raise questions. In some cases, the shareholder (private or public) expresses contractually and organisationally his non-intervention in the editorial policy of his medium, to preserve its value. He may decide in collaboration with the editor to add vigilance tools such as a supervisory board. Or, on the contrary, he can refuse to allow editorial teams to implement a code of ethics and cause entire editorial teams to resign when they no longer feel free to work. To examine more closely the reality of the independence between the shareholder and the editor, one may wonder whether the holder of a media can or has already imposed a subject, had a subject or an article deleted, or dismissed a journalist. We can check whether he has a political agenda by comparing the speaking time allocated to a particular party and his involvement in an election campaign. We can also see if the media covers its shareholder (private or public) and in what terms.

How does the media finance its activities?

Is the media financed by its subscribers or by donors, by its individual sales, by a tax, by advertising only, by a mix of all this, by aids and subsidies, by commercial agreements with platforms, search engines and social networks?

Very few media are profitable only because of their readers or donors. These media are most often media recognised for their investigations, their exclusive information or their specialised subjects who also have shareholder structures to protect the independence of their editorial staff.

The budgets of the public audio-visual media are voted each year and defined in the framework of multi-year contracts with the French State. The election of their CEO is based on a project reviewed by Arcom (formerly CSA)–The Regulatory Authority for Audiovisual and Digital. Even if we do not imagine that the “wise” can choose a candidate who does not have the favour of the government, the State in France is more interested in the budget than in the editorial line of these media.

Most media have adopted a mixed model based on advertising revenues and subscription revenues. When a company or an institution–the advertiser–finances a significant proportion of a media’s activities, one may wonder whether the editorial staff will not be self-censored or prevented from being able to investigate. In addition, an advertiser’s threats to a medium through the freezing of its advertising budget are regularly revealed in specialised or investigative media. If it is not illogical to expect a company to try to put pressure on a media outlet, we have to ask ourselves whether those media outlets have abandoned their investigation or not to disseminate information. Hence the importance of checking whether the media in question is authorised to cover its advertisers, or not, and in what terms. Hence the importance also of the diversity of securities and especially of their financial health to invest in the survey and possibly to do without the advertiser whose pressures are proven, as was the case for HSBC at the time of the Swissleaks in 2015, or, it seems, for the Vivendi group via its agency Havas after the publication of two investigations in Le Monde in 2014, or again with LVMH joined by other brands after Libération's provocative front page and article on Bernard Arnault in 2012.

These reflections continue with diversification activities–particularly in terms of event co-production and the creation of content such as native advertising or brand content for labels–and media partnerships with platforms. In various capacities (launch of new products, financing of the fight against fake news), platforms have become very important actors for the financing of many media. Although GAFAM clearly indicates that it is not involved in the editorial policy of the media, the platforms fund certain media to create news products specifically to meet their needs and those of their users.

How is the media distributed?

We do not necessarily know it, but it is not the newsvendor that chooses the titles he presents to his customers in his newsstand. In order to guarantee citizens access to the plurality of views and political, economic and other analyses, the law requires that these newsstands distribute all media in an impartial manner.

These constraints, very strong, for a distributor (not to choose his traffic, not to be able to negotiate with his suppliers) do not exist on the web. Last year, only 23% of a media’s online audience was live; and 77% of its audience came from search engines, social networks, and to a lesser extent from aggregators, mobile alerts, and newsletters.

Given this proportion, media dependence on platforms seems vital to draw traffic to their site. As such, the technological and human investments made by the media to be well indexed by search engines and active on social networks are colossal. On a daily basis, the editor of an article for the web cannot ignore Google when he is about to validate his title and click on “publish.” However, platforms remain the only judges of their SEO policy, content visibility, and partnerships can change overnight.

The “neighbouring right” as it is coming into force between platforms and publishers will reinforce this dependence between the world of tech giants and that of press publishers in Europe. Calculated on the basis of the usage performance (audience, clicks, page views) of media content in search engine and social network services, they will pay a fee to publishers called “neighbouring right” of copyright. Logically, it is the media that have been able to invest massively in their technological tool and that best respect the codes defined by the engines and networks to be present on the platforms that will be the most remunerated and that will therefore be able to reinvest... leaving the plurality of the media (and the diversity of their investment capacity) on the roadside.

Conclusion

Every time we discover a new medium, we have to ask ourselves what measures it has put in place to protect its journalists from attempts to influence. Are the information verification and validation processes clear and respected? Is there a code of ethics? Are there safeguards when errors or breaches are identified? Are there procedures to deal with them? Have they already been applied?

Various projects to certify or label the media have emerged in recent years. Will they be able to help rebuild trust between the media and citizens? All initiatives must be reviewed at a minimum. These few lines are intended to show some elements of the debate on the independence of the media. Information is a subject that generates so much affect that we often tend to confuse quality of information and editorial line; Any article that does not correspond to my vision of the world and its issues is biased or even misleading. The plurality of worldviews is resolved with the diversity of titles. The legislator tries to guarantee it through laws that set thresholds for holding media, direct and indirect aid, inventory of newsstands... All these rules remain largely to be invented on the Internet.

In order to be sure that one cannot be suspected of dependence on third parties, in theory a media company should not belong to a physical personality that is not a journalist or to a group that does not have only media, it should not be able to finance itself other than through subscriptions or donations, not resort to any State aid or subsidy, exclude any commercial contract with the platforms, probably finally refrain from publishing on social networks and proscribe its articles and videos from search engine results.

Media that meet all of these criteria do not exist. Those who meet the majority of these criteria and are beneficiaries can be counted on the fingers of both hands. They have every reason to congratulate themselves on that. Does this mean that all other media provide biased information to their readers? These few reflections may have helped us understand a little better why it is difficult to talk about the media and their independence in general. They do not aim to praise the profession and even less all the media, but to allow them to better orient themselves in the burgeoning panorama of the media, to consider some reasons that justify the differences in quality in the treatment of information of one or the other, and also to spare our expectations. For this reason, it seems to me, it would be interesting to use the term “independences” of the media in the plural to discuss this concept and its realities in a more peaceful way. Or even to propose another criterion, that of “transparency”, to establish with our readers a “contract” which is based on more objective, stronger, and finer bases.

Resources:

Barometer Kantar – La Croix

Digital News Report 2022 – Reuters Institute

Published on November 21st, 2023

About the author:

Benjamin Sabbah is the managing director of Worldcrunch media and teaches media economics at ESJ - Sciences Po Lille. He previously held various sales and marketing positions at Agence France-Presse (AFP).