This article is part of Reset! Yearly Focus 2025: Reclaiming Spaces

Author: Amar Patel

Grassroots cultural venues across Europe are facing escalating costs, rising inflation, and the long tail of capitalism that demands competitiveness. How can they build a business on solidarity? Is that approach financially sustainable? And what would a cooperative economy look like?

The Brookdale Club in Catford (South East London), which will reopen as Sister Midnight, Lewisham's first community-owned music venue – © Sister Midnight archives

The other week I came across two infuriating bits of news. The first is that the richest 10% on the continent own a staggering 67% of wealth, while the bottom half of adults possess only 1.2% of it. Inequality has been on the rise for decades but that is a disgraceful chasm.

Secondly, Thames Water, who supply about a quarter of homes in England, have increased prices by around 40% for unmetered customers after racking up £19 billion (€23 million) of debt and “routinely” releasing sewage into rivers.

This is the same Thames Water who in 2023 paid out £196 million (€234 million) in dividends to its holding company to service debt. Now the customer will have the foot the bill for years of chronic underinvestment and “financial mismanagement”.

What’s all this got to do with arts and culture? Well, what connects these two gripes is economic and social injustice. One is an egregious accumulation of power and the other is a clear abuse of it.

Elites consolidating capital at the expense of the less financially secure has far-reaching consequences, as Dr Sarah Kerr and Dr Michael Vaughn outlined in a 2024 report for The Joseph Rowntree Foundation. “Wealth inequality fuses together many of the defining challenges of our present moment: climate, social cohesion, trust in government, institutions and democracy.

“The very wealthy can use their resources to influence politics in ways which ultimately protect their assets from redistribution. Wealth generates power, which is used to protect wealth, creating an ‘inequality trap’.”

Aside from raising tax, how might we counter this? Kerr and Vaughn propose “the development of new or public assets, or through the re-commoning of previously privatised national assets”. In other words, more equitable forms of ownership like cooperatives.[1]

The transactional, extractive, exploitative nature of business begins to fall away when cooperation is placed at the heart of trade and governance as Cliff Mills, solicitor and veteran of the UK cooperative movement, explains.

“To describe cooperation as an alternative to contracts may sound strange,” he admits. “But through cooperatives, you can create communities of customers, workers or traders… Cooperation is a way of opting out of the market and setting up your own ground rules for enterprise.”

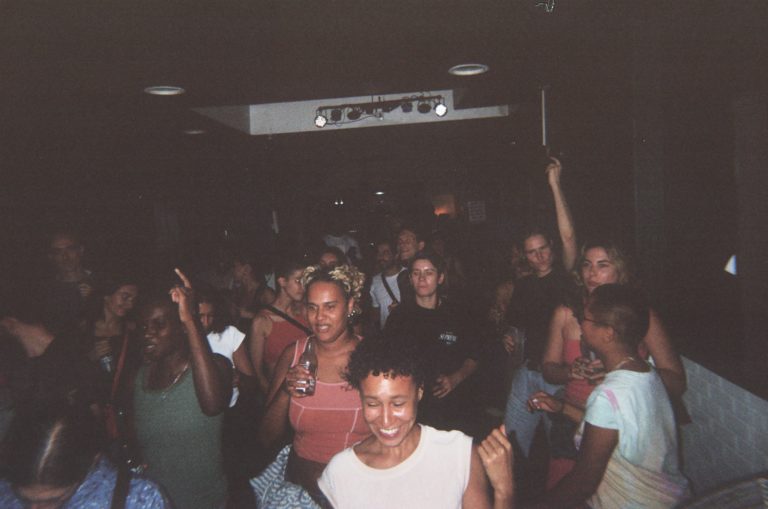

Audience at a past Sister Midnight community meeting in Catford – © Sister Midnight archives

Cooperative Venues

Democratic governance, shared ownership, mutual benefit… If you want to run an organisation with a social purpose, the appeal of a cooperative is plain to see. But what makes it particularly attractive to someone running an arts or cultural space? Who better to ask than Lenny Watson, a founding director at Sister Midnight, who are opening Lewisham’s first community-owned music venue in South-East London next year.

“For the longest time we’ve seen our local venues closing down or getting bought by big commercial operators and turned into pubs and gastropubs,” Watson explains. “I think people feel really helpless in that situation. So the idea that a venue could be protected by this element of community ownership feels very important.

“People are just bored of old capitalistic models of having companies owned by a few individuals who kind of extract the value of workers’ labour and hoard the profits. That’s not really what communities want, especially ours. They want to have a say and they want to be part of something.”

Sister Midnight used to be a sole trader company and had considered becoming a non-profit for some time. Watson looked more closely at cooperatives during lockdown and knew straight away it was the right fit for their next phase. Community ownership and investment were particularly enticing elements, as was succession planning.

But there were more options to consider. “We have two legal structures for cooperatives in the UK: a Cooperative Society and a Community Benefit Society,” she explains. “What makes us the latter is the fact that we are also run in the interests of the wider community.”

Watson demonstrates how by taking me through key aspects of Sister Midnight’s governance. “We have our core team of staff members who do the day-to-day work and make a lot of the decisions. We have our board, which includes some members of staff like myself, but also others who have been elected. They make sure we are meeting our targets and doing things in the right way.

“Then there is our community advisory committee, which is voluntary and like a sounding board for the board. It’s important for us to have the broadest demographic represented in our decisionmaking.

“Most importantly, we have our members – around 1,000 locals [and others beyond Lewisham] who have bought shares in Sister Midnight. They have a say on key issues at the annual AGM and throughout the year.

“That balance is working for now but we are always opening to evolving our model. I think that’s a really exciting thing about being a cooperative. We can be agile and adapt as things change.”

That is exactly what club coop have done in Marseille, developing their own approach in a very flexible and exploratory way. What research coordinator George Trotter describes as a producer-consumer cooperative structure, in which participants become members with a financial and decisionmaking stake.

“This system would function through a relatively nominal financial contribution and a more substantial service contribution (like working on the door, helping with sound and lighting or moderating online spaces).”

club coop's George Trotter signing up new members of the door – © club coop archives

A key goal was to provide a platform to artists from Marseille’s marginalised or otherwise underrepresented creative communities, offering them fairer fees while making it affordable for fans.

Between May and December 2023, they ran a pilot programme in a rented space close to the centre of the city, funded by a grant from the Creative Impact Research Council Europe (CIRCE). “Our focus was on testing the decisionmaking and member shift components,” says Trotter.

It all began with a coordinating committee of him, community manager Ana Sanz, and operations coordinator Vincent Kulesza. Like Sister Midnight, they recruited a community advisory board who met weekly to propose, review, and sense-check policy covering anything from programming, publicity, and financial matters to safer spaces and membership. Or as Trotter has also phrased it, to create “systems of cooperation.”

A mark of the board’s integrity is that members could, and did, vote against their own self-interest. For instance, raising drinks prices after realising that club coop’s residency agreement (which stipulated they had to give at least a third of the bar take to the landlord) and restrictive opening hours made initial prices unsustainable. It showed “a willingness to prioritise the needs of the project,” says Trotter, “which is crucial for long-term viability.”

After attending the opening, which attracted around 200 people, one member proposed bringing together up-and-coming hip-hop artists from neighbourhoods in Marseille (Frais-Vallon) and Paris (Montfermeil), who are facing similar socioeconomic challenges.

OMR doubted whether any of the Marseille contingent had “ever played in the centre” prior to the event, and none of the artists had previously received a fee for their performance.

Between September and December 2023, club coop booked more than 60 local artists and paid over €7,000 to creative professionals, supported by more than 700 members and 1,000 unique attendants, many of whom have made lasting connections there.

Opening night at club coop in Marseille, September 2023 – © club coop archives

Big Wins and Tricky Hurdles

What have been some of Sister Midnight’s key successes so far? “Finding a venue,” Watson replies without hesitation. “I have been working in music in South-East London for the last eight or nine years and I have been looking for spaces that entire time. The fact that we got a venue and then convinced the local council, who own the building, to give it to us rent free for 10 years … I’m still reeling from that!

“Also, just the amount of community investment we have raised, more than £350,000 (€420,000). To have so many people involved in building this new space with us, it’s a real testament to our community and their perseverance.”

Although the venue (an old working man’s club) is still being renovated, Sister Midnight has been putting on events in nearby spaces including not-for-profit Piehouse, and developing a community radio station.

“It’s really important to us to get people involved who might not typically have access to culture,” says Watson. “We do this through programming but it’s also things like affordable ticket schemes or inviting people to come and just pay what they can … even if that’s nothing.”

As big as these wins are, they don’t assure success. It’s taken more than four years to get to this point and the life of a cooperative is never less than precarious. What have been some of the biggest hurdles for Sister Midnight? “Money and local authority bureaucracy,” says Watson. “Working with the latter is really slow and that’s not how we like to work. So it’s been a little frustrating to be held back by that.

“But money is the big one. It’s been hard to get funding because we aren’t trading properly at the moment. I wish there was more funding available for people like us who need it over a period of four or five years to get things off the ground.”

Trotter agrees that “a bit of funding goes a long way”. It helps you to plan and project into the future, though venues would be wise to develop diverse revenue streams in parallel with funding applications. club coop are also speaking to local authorities and looking for a permanent space as renting month to month “just wasn’t tenable with the budget we had”.

Over in Budapest, another purposeful organisation is also trying to reconcile its altruistic mission with the commercial reality of mounting expense and limited state support. Auróra describes itself as “a social enterprise which was created to connect cultural programmes, civil and activist organisations’ work, community building, and fun.”

“It’s a safe space for individuals from less privileged or sensitive social groups, and the organisations representing them,” explains managing director Blanka Rákos. She gives two examples: The School of Public Life (a grassroots civic education centre founded in 2014, dedicated to building a democratic and just Hungary) and Szivárvány Misszió Foundation, which organises Budapest Pride.

An educational programme in Auróra's Climate Garden – © Auróra archives

The house occasionally offers use of the premises free of charge and can assist with catering, production, and promotion of events. Visual artists, bands, and “dedicated youngsters” can also showcase their work. Another important strand is collaborating on major events including Bánkitó Festival.

Although successful in their mission, Auróra’s good work has not translated into financial sustainability. In fact, they live in constant uncertainty, not least because the owner of their site wants to sell, which is forcing them into “a complete redesign”.

So severe are the economic challenges in Hungary, that Rákos says their greatest success has been making it to their tenth anniversary last year. The combined effect of rising inflation and costs, stagnant revenues, chronic underfunding, COVID-19, and cash-strapped clientele has placed significant pressure on operations. In an effort to pursue more tenders, they converted from a limited liability company to a non-profit in 2024.

There are also more nefarious forces at play as they try to survive in what Rákos describes as a hostile environment. “The house has been subjected to numerous political attacks and has been closed down multiple times by the local Fidesz using unjustified pretexts,” she says.

“For over 12 years, Hungarian politics on the government's side has been constructing an enemy image against which they constantly incite the gullible masses: the ridiculing of LGBTQ+ rights (conflating them with paedophilia), inciting against immigrants, and forcing women to have children. All while the state of education and healthcare are steadily deteriorating.”

Ballroom party at Auróra – © Auróra archives

Towards a Cooperative Economy

But, what if a cooperative could feel more nurtured and cultivated, and not have to fight for survival? Under what conditions might it flourish and become part of a wider economy? Cliff Mills has a few thoughts from a legal perspective.

“We, and I include myself in this, have spent too much of recent decades selling a structure…” he told a Society of Cooperative Studies gathering in his keynote speech back in February. “We should be selling cooperation, not cooperatives.”

By that, he means “a framework for facilitating trade for the benefit of human beings today and for future generations”. One that is established for the common good over private gain, and distinguishes member transactions from those on the open market.

He cites places such as Italy where “profits from member transactions allocated to indivisible reserves in Italian cooperatives are not subject to corporation tax. This has resulted in large amounts of capital being accumulated which has funded the sort of growth that we [The UK] can only dream of.”

Emilia-Romagna is a shining example of what’s possible. A region characterised by shared prosperity and relatively low inequality, where 15,000 out of Italy’s 43,000 cooperatives are based, according to this report. GDP per capita is 20% higher than the rest of Italy and 17% higher than the EU average.

In 2023, CCIs represented 4% of the economy in the area. Emilia-Romagna is a net exporter of culture and creativity (12.9% in 2022 in a region where only 7.5% of Italians live).

Where lawyers can help, says Mills, is by “finding ways to facilitate cooperation alongside existing contractual arrangements, so that citizens have a genuine choice about who they buy from, who they work for, and where they keep the money which they don’t need today.”

Kieron Boothe playing at Sister Midnight's May 2025 show at Piehouse CO-OP – © Sister Midnight archives

TOP TIPS FOR COOPERATIVES

"Don’t be afraid to just jump in with no knowledge or experience because you can still do amazing things just by having drive and energy.”

-Lenny Watson, Sister Midnight

"Test and refine ideas through experimentation. You can rework plans on the fly, especially with all the tools available to quickly collect and evaluate member input."

-George Trotter, club coop

"Make connections [with other cooperatives and non-profits], both domestically and internationally, with whom you can jointly apply for funding in pursuit of similar goals.”

-Blanka Rákos, Auróra

References

[1] The International Cooperative Alliance (ICA), an independent and non-governmental organisation that represents three million cooperative enterprises and 140 million members, say that “Cooperatives are owned, controlled and run by and for their members to realise their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations.” [Each member having one vote, regardless of the capital they invest.]

Published on June 19th, 2025

About the author:

Amar Patel is a London-based writer who has worked with Factory International, The British Library, Straight No Chaser, The Quietus, Lexus and Clear Channel. He also mentors at the Ministry of Stories, with Arts Emergency and is a director at Sister Midnight.