Author: Manon Moulin

Kosovo's recent elections, its 17th independence anniversary, and ongoing political and economic challenges highlight the resilience of its independent cultural and media scene, which faces funding cuts, political interference, and external pressures while striving to foster community-driven sustainability and cross-regional collaboration. To get the pulse of the independent scene, we interviewed Besa Luci, editor-in-chief of Kosovo 2.0, an independent print and multimedia multilanguage magazine, as well as Sadie Suhodolli, aka Tadi, visual artist, DJ, and co-founder of the Bijat collective, an organisation pushing a feminist and queer perspective in the electronic music scene.

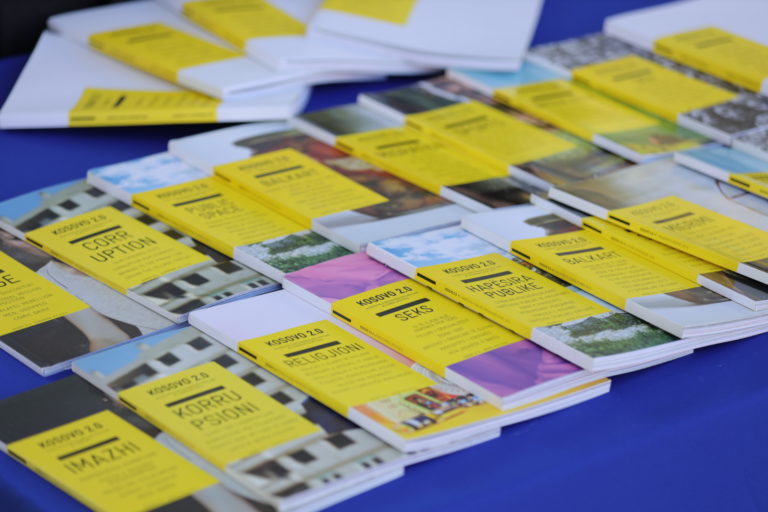

© Kosovo 2.0

On February 17th, 2025, Kosovo celebrated the 17th anniversary of its independence. This milestone comes a week after the young country’s last parliamentary elections, which took place on February 9th. The first regular elections in the country’s history—meaning that the government has completed its full term—saw the incumbent candidate, Prime Minister Albin Kurti, and his Vetëvendosje! Party (VV) came first with more than 40% of the vote, but lost the majority they won in 2021 with more than 50% of the vote. This election and its campaign took place in an overall national and regional context of tensions and political interference that deeply affect independent Kosovan cultural and media players.

Kosovan Citizens Won’t Be Fooled

It's important to note that the current election results are not entirely final, partly because the Central Electoral Commission (CEC) has a month to officially certify the results, and partly because the same CEC “vote counting updates were halted,” says Besa Luci. Votes are hence still being counted, particularly from the diaspora, conditional ballots, and those cast by people with disabilities. However, it’s unlikely that the currently announced results will change drastically.

As Besa Luci says, this election “indicate that citizens are increasingly holding politicians accountable, both within the ruling party and the opposition.” Indeed, among the main parties, only the VV has seen its score fall. One explanation could be that the ruling VV published a very light programme and its candidate, Albin Kurti, refused to take part in media debates. This aloof attitude didn’t convince all 2021 voters to give their vote to VV again, which has been “criticised [for] attempt[ing] to avoid public accountability,” as Sadie Suhodolli explains.

“Citizens cannot be taken for granted,” says Besa Luci, and media coverage of these elections, and of politics in general, tends to be “personif[ying] politics, emphasising individual leaders rather than providing thorough, in-depth reporting, analysis, or even fact-checking”–a situation that is of course not specific to Kosovo. This lack of in-depth and informed political coverage doesn’t represent the needs and interests of the Kosovan population, which is largely preoccupied with socio-economic well-being. Unfortunately, the latter partly depends on regional politics, especially on Kosovo-Serbia relations, in which the EU is heavily involved.

Bijat at Karmakoma, nightclub in Belgrade – © Nani Pavlovic

Political and Economic Interference

Relations between Kosovo and Serbia are at the centre of regional politics, mainly because Serbia doesn’t recognise Kosovo as an independent State. Since Kosovo’s declaration of independence in 2008, various agreements have shaped relations between the two countries in an attempt to normalise them. This process has been conducted mainly under the supervision of the EU and, to a lesser extent, the US and international institutions.

However, without going into the details of this very complex situation, not all parties are playing the game, but some are suffering the consequences more than others.

The example of the Ohrid Agreement is eloquent. This agreement, also known as the agreement on the path to normalisation between Kosovo and Serbia, fits into a broader framework of an EU-led approach to normalisation that started in 2013. The agreement was accepted by both sides in October 2023, by Albin Kurti for Kosovo and Aleksandar Vučić for Serbia, but Vučić refused to concretely sign it, claiming that more discussions were needed. For its part, the EU asserted that the verbal agreement was binding enough–a questionable stance. This was preceded and followed by various violent incidents in northern Kosovo, notably an armed attack organised by the former vice-president of Srpska Lista, a Serb minority political party in Kosovo, in which a police sergeant was killed, and violence related to the refusal of the Prime Minister Kurti to allow the establishment of the Association of Serb Municipalities in northern Kosovo.

In this context, the EU has imposed sanctions on Kosovo for ‘failing to maintain peace in northern Kosovo’, but has not sanctioned Serbia for its involvement in the violence. This “double standard in the EU’s approach,” as formulated by Besa Luci, tends only to push the actors away from the normalisation table.

It also has a deep economic impact on Kosovo, as all EU funds are frozen under these sanctions. On top of this, with USAID shutting down under the new Trump administration, the US have recently cut off many flows that contribute to the development and stability of Kosovo’s economy, but also to the viability of its cultural and media scene. Indeed, Sadie Suhodolli shares her hope that this moment will “put Kosovo officials into trajectory of finding sustainable and independent modes of securing funds from its own budget to at least sustain main cultural life of the country.”

© Kosovo 2.0 print covers

Independent Culture and Media Lacking Support

As in most countries, culture and media are usually the last to be considered, and even more so when it comes to independent culture and media. And in Kosovo, this situation is made even more fragile by the fact that external actors have decided to abandon the country and its scene by withdrawing their economic investments, but also because of political pressures on national funds distribution.

In 2023, the EU is said to have taken away around €500 million from Kosovo, while the US, mainly through USAID, distributed $70.3 million in 2023, which will disappear in 2025. These suspensions have “forc[ed] many organisations to cut staff and halt crucial services,” explains Besa Luci. One of these victims is the Lumbardhi Cinema in Prizren, which had to cancel its renovation after its €1.5 million grant was frozen. And when a grant isn’t frozen, it is the EU bureaucracy which is “discourag[ing] people in applying due to gigantic application processes, for which small scene like Kosovo don’t have manpower for,” points out Sadie Suhodolli.

On the other hand, Sadie Suhodolli explains that the national funds are in the turmoil. Despite growth in funding, there is an increased anxiety within the independent cultural scene regarding a possible “politisation of funding,” regardless of which party will come to power. Both situations weaken the infrastructures of Kosovo’s cultural sector by making them conditional and unreliable.

Being an independent cultural or media organisation in Kosovo now means being self-reliant and trying to create stronger links directly with the audience. This is what Kosovo 2.0 is trying to do with its membership programme HIVE; “foster[ing] both independence and a stronger connection with audiences,” as Besa Luci says. This is also the case with the Bijat collective, which itself exists thanks to its community of like-minded DJs and artists. The latter are even a great example of overcoming political divides between Serb and Albanian community in the region. Indeed, Sadie Suhodolli takes the example of the Mirëdita, dobar dan! festival: “it brings together artists, human rights activists, peace activists, and public figures from Kosovo and Serbia, and contributes to a regional perspective and fosters cooperation and peace building.” She continues by explaining that “electronic music scene from both sides has been collaborating with each other for years.”

Independence celebrations, election results, and economic instability have been the rhythm of Kosovan life in recent days, weeks, and years. Despite these challenges that push young journalists and artists to leave Kosovo, the country “still has a very vibrant independent scene with youth movements and media initiatives that are striving to contribute to a better cultural social environment,” concludes Sadie Suhodolli. As Europe’s newest country paves its political way, its independent cultural and media scene is indeed trying to find its place to exist without surviving, and it looks like the answer is once again collective, with the community of each project at its core.

References:

Parliamentary election in Kosovo: What you need to know – Deutsche Welle

Preliminary election results 2025: in context – Kosovo 2.0

Multilateral declaration of independence of Kosovo – Koha

Kosovo feels the pain of EU sanctions as election looms – Reuters

The History & Music of Kosovo’s Queer Ballroom Scene – Bandcamp

Surviving Kosovo’s Crowded Media Landscape Series by Gentiana Paçarizi – Reset! network

- A Country Without Print Press

- Online Journalism in Kosovo: A Search for Sustainable Survival

- Local Journalism at Risk

Published on February 20th, 2025

About the author:

Manon Moulin is the editorial coordinator of all European projects for the non-profit organisation Arty Farty. She specifically works on the European network of independent cultural and media organisations Reset!, as well as the aggregation media We are Europe.